Are you thinking about your bone health in Parkinson’s? You should be!

Parkinson’s disease is commonly accompanied by soft or brittle bones. Parkinson’s disease affects more men than women and people tend to forget about monitoring bone health in men with this neurodegenerative condition. In this month’s blog we will dig deep into the osteoporosis challenge in Parkinson’s disease. I will recommend proactive strategies you can use to strengthen your bones.

What is the most common bone abnormality in Parkinson’s and why do we care?

Following a bone scan many persons with Parkinson’s will be shown to have a reduction in their bone mass density. We care about the bone mass density because a low bone mass density is an important factor in how often a bone is broken. The mobility and balance challenges of Parkinson’s disease increase the risk of broken bones (fractures). You should therefore be ‘proactive’ about strengthening the bones if you have Parkinson’s.

What is the difference between osteoporosis and osteopenia?

The terms are defined by the severity of bone loss and also by the risk of future bone fractures. Osteopenia is when the bone mineral density is lower than when compared to a normal person. Osteoporosis is when there is a significantly reduced bone mineral density along with weakened bone structure. A diagnosis of osteoporosis carries an increased risk of broken bones also referred to as fractures.

The terms are defined by the severity of bone loss and also by the risk of future bone fractures. Osteopenia is when the bone mineral density is lower than when compared to a normal person. Osteoporosis is when there is a significantly reduced bone mineral density along with weakened bone structure. A diagnosis of osteoporosis carries an increased risk of broken bones also referred to as fractures.

What are the risks to your bone health if you have Parkinson’s disease?

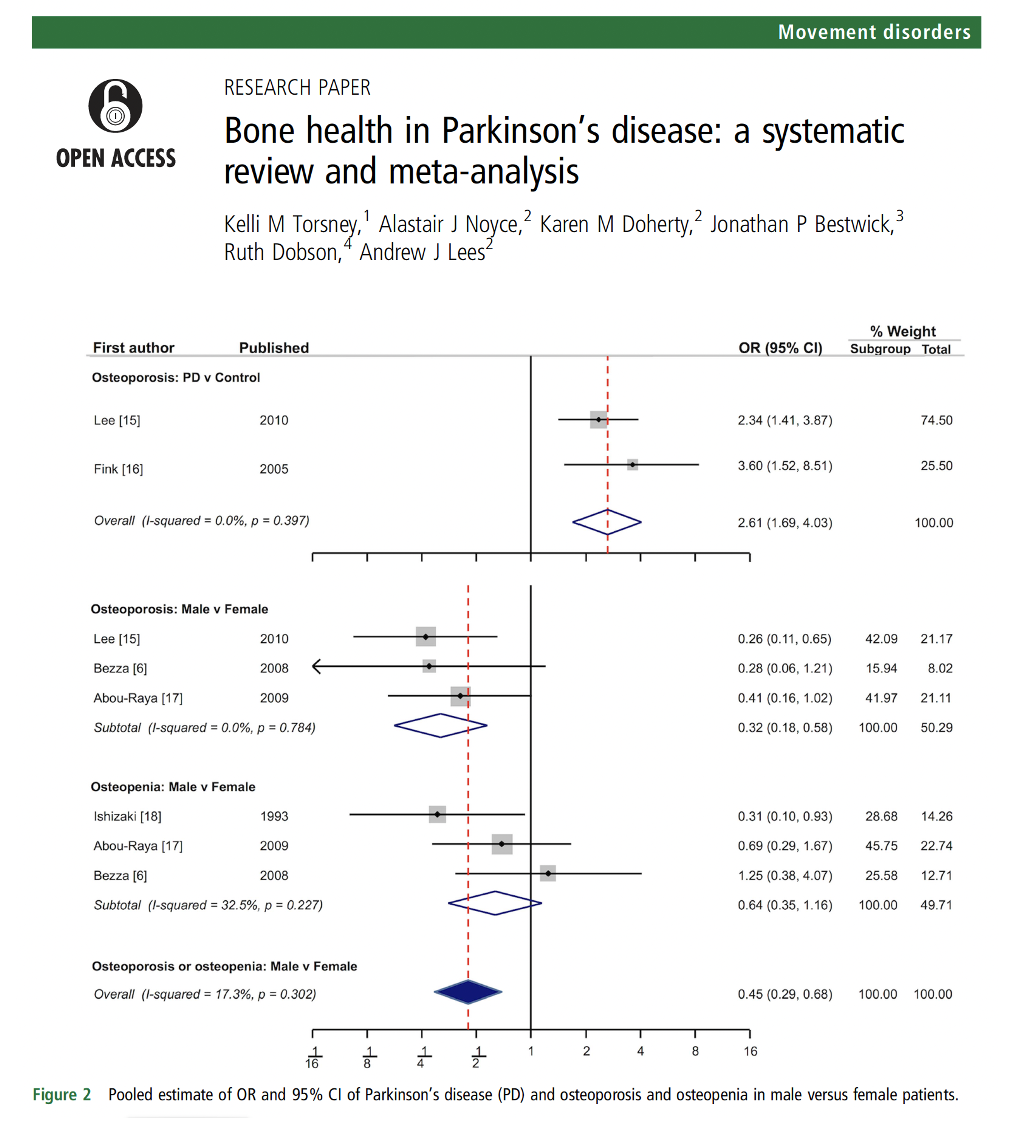

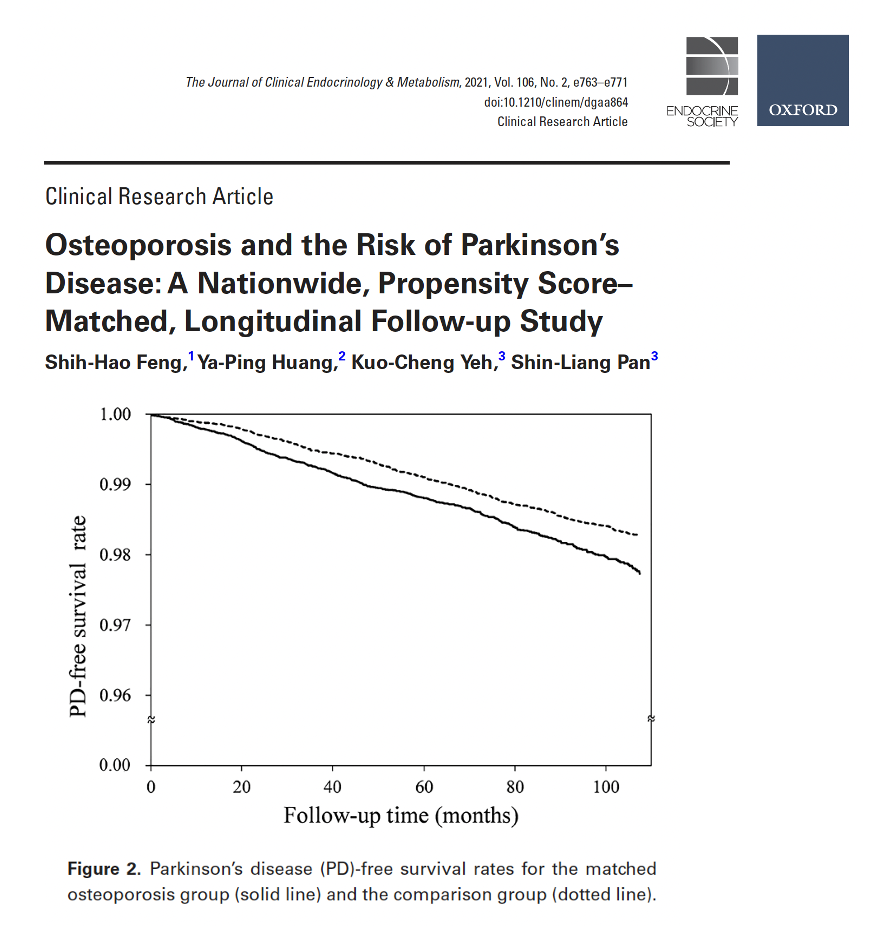

Torsney, Lees and colleagues explored the risks of bone health in Parkinson’s disease in their 2014 article. The authors reviewed 23 relevant studies and their results were published in the Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. The bottom line was that if you have Parkinson’s disease, the risk was much higher for osteoporosis (OR 2.61; 95% CI 1.69 to 4.03) and it was estimated to be DOUBLE when compared to a normal age matched population. The risk was present for both men and women with Parkinson’s disease, but was greater for women. Further, Parkinson’s had an increased risk for fractures (OR 2.28; 95% CI 1.83 to 2.83). Another study by Feng and colleagues in a Taiwanese cohort (2020) showed that those diagnosed with osteoporosis had a slightly elevated risk of later being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. They also showed a potential increase in mortality in those with Parkinson’s and osteoporosis.

Should your fracture risk be assessed with a screening tool?

Yes. There are many simple screening tools which can be administered to determine your fracture risk. One commonly used international tool is called the FRAX. Unfortunately, the FRAX and other available tools do not specifically address Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s related falling.

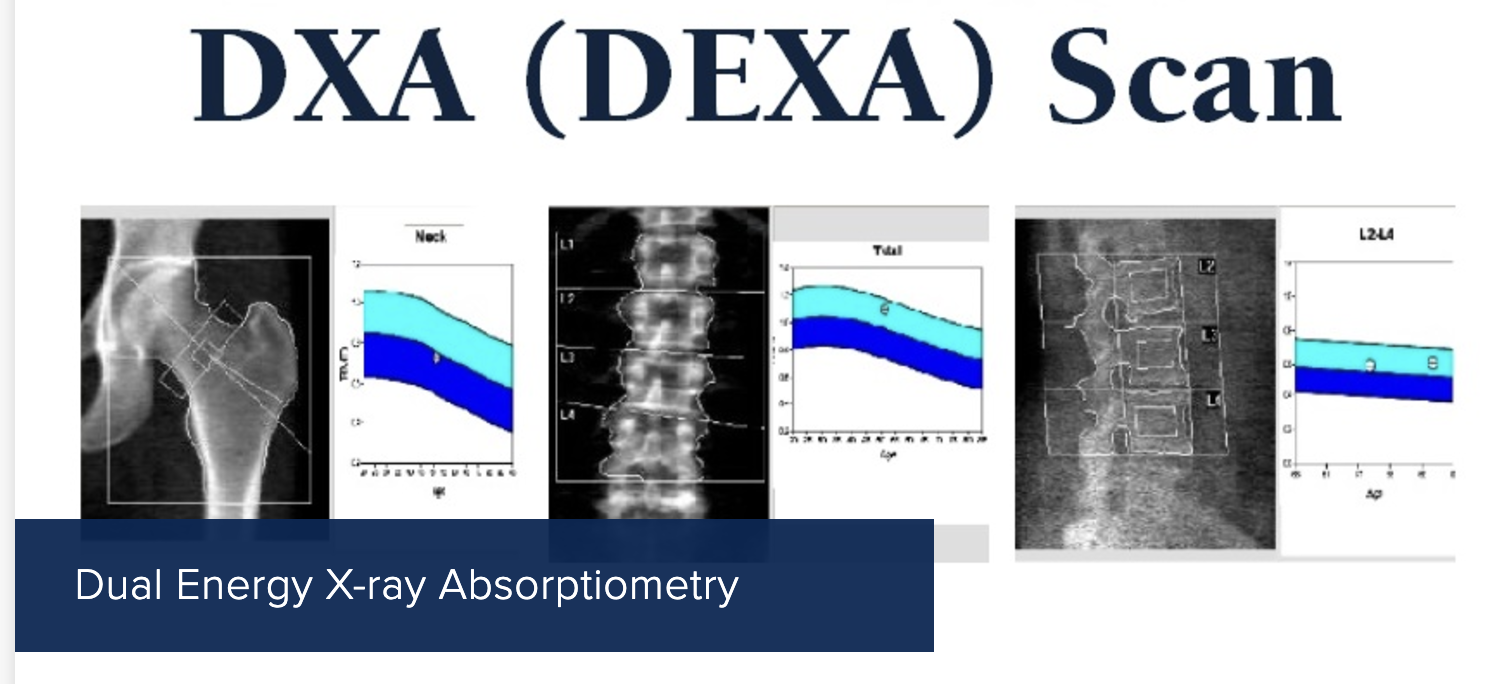

What is a DEXA scan and why do I need one if I have Parkinson’s?

A DEXA scan is called dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. The test measures a your bone mineral density. Your doctor or health care professional will share the results with you in something called a T-score. A normal T-score is -1.0 or greater. If you have a diagnosis of osteopenia, the T-score will be between -1.0 and -2.5. Finally, if you have osteoporosis, the T-score will be -2.5 or lower.

Is a DEXA bone scan safe?

You should know that a DEXA scan is considered a safe and non-invasive procedure. It uses very low levels of X-ray radiation. The radiation levels are lower than in a common chest X-ray or a computed tomography (CT) scan. Experts have estimated that the dose of radiation from a DEXA scan is comparable to the radiation you receive during the course of a typical day. The scan takes about 20 minutes, and there are no injections, incisions or contrast agents. Pregnant women are advised to avoid DEXA scans (if possible).

What are the symptoms of osteopenia?

Frequently, this condition is asymptomatic and you would not know you have ‘soft bones’ without performing a test such as a DEXA scan.

What are the symptoms of osteoporosis?

Like osteopenia, osteoporosis can be invisible. If your healthcare team finds fractures in the hip, spine, or wrist, these may be important clues. Some folks with osteoporosis may lose height or take on a stooped posture. Since Parkinson’s can also be associated with loss of height and a stooped posture, screening with bone density scans is considered especially important.

What are the possible risk factors for bone loss?

The risk factors for osteoporosis include aging, menopause, nutritional deficiencies and not walking enough (referred to by doctors as being sedentary. Smoking, drinking alcohol and taking corticosteroids can all put you at risk for soft bones. Osteopenia and osteoporosis have been shown to be associated with chronic illnesses such as Parkinson’s disease.

Is your muscle health important to prevention of osteoporosis and osteopenia?

We think the answer is yes. Lima and colleagues, in a recent study, revealed an association between lower lean appendicular mass and osteoporosis. Most experts agree that paying attention to exercise, muscle mass and muscle quality will all be an important to your bone health in the setting of Parkinson’s disease. The authors of this study teach us that “muscles and bones share common anabolic pathways, and muscle-derived factors, such as irisin, (and these may) directly influence bone metabolism.”

How do you apply clinical practice guidelines for treatment of bone loss to Parkinson’s disease?

Mícheal Ó Breasail and colleagues recently performed a systematic review of the treatment of osteoporosis and osteopenia in Parkinson’s disease. The authors identified 6 relevant papers that contained recommendations for bone health in Parkinson’s disease and they addressed clinical practice guidelines, consensus statements, and treatment algorithms. Bone health was recognized as important by all 6 teams writing on this topic. The authors found it surprising that “recommendations for fracture-risk screening were inconsistent.” Only one paper addressed the “acceptability and tolerance of anti-osteoporosis medications” when administered in the setting of Parkinson’s disease. This paper did incorporate “national osteoporosis guidelines into a Parkinson’s disease specific treatment algorithm.”

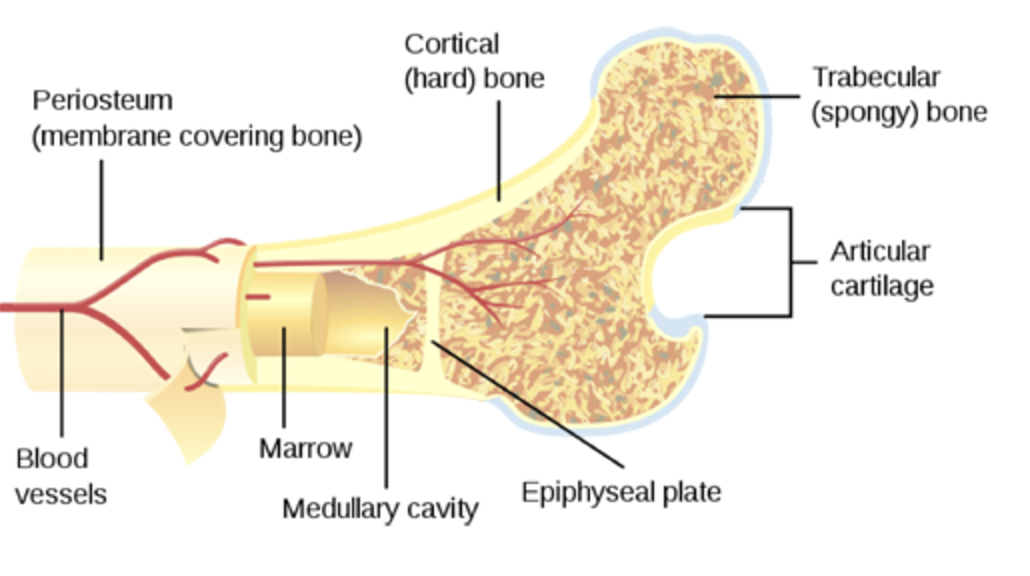

What happens to your bones as you age?

[image]

What is known about the association between bone loss and Parkinson’s?

The degenerative brain process in Parkinson’s disease affects important circuitry for bone health. Many published studies have revealed a higher prevalence of osteoporosis and osteopenia in persons with Parkinson’s. The immobility and reduction in overall physical activity in the setting of Parkinson’s disease, place both men and women at risk. Additionally, vitamin D deficiency is common in Parkinson’s disease. Addressing vitamin D deficiency with sunlight is a double edged sword, as there is an increased risk of melanoma if you have Parkinson’s disease. Studies have revealed an altered metabolism of calcium which can reduce bone thickness. The Parkinson’s medications such as dopamine agonists have been thought to also reduce bone density. as dopamine has been shown to be important to remodeling of bone. Finally, a reduction in estrogen or testosterone levels also contributes to bone loss.

Researchers have been interested in whether inflammation can impact bone health in the setting of Parkinson’s. Experts have opined that it is possible that inflammation stimulates osteoclast activity (cells that break down bone) and inflammation reduces osteoblast activity (cells that make new bone).

Do brain degeneration and dopamine drugs contribute to bone loss in Parkinson’s disease?

We think so. The degenerative process in Parkinson’s includes brain regions critical to brain related pathways that are important to bone health. Much of what we know today on this topic has been learned from animal experiments. In animals experiments, Handa and colleagues in a 2019 paper in the journal Scientific Reports, showed that bone metabolism can be mediated by the dopaminergic system and that hormones and administration of dopamine drugs play a role. Important work remains to be done to clarify the degenerative processes leading to bone loss and the effects of dopaminergic medications.

What are my treatment options if I have osteopenia or osteoporosis with my Parkinson’s?

The best place to start for addressing osteopenia is to change lifestyle. Improving calcium and vitamin D intake are imperative, and adding weight-bearing and strength-training exercises can also be a critical component to avoid futher bone loss. If you smoke or drink it is time to consider quitting..

If you are diagnosed with osteoporosis, in addition to the above considerations, your health care professional should discuss the risks and benefits of bone strengthening medications including bisphosphonates, denosumab, and possibly hormone-related therapies.

What drugs have been associated with a potential risk of bone fractures?

Drugs that have been associated with falls and fractures include antidepressants, dopaminergic drugs, drugs that block dopamine (neuroleptics), and benzodiazepines, along with other anti-anxiety agents. It is important that if you have Parkinson’s, you should appreciate that the association of these drugs does not automatically translate to the drugs ‘causing bone fractures.’

Here is a nice table of some of the drugs listed in the publication US Pharmacist known to be associated with hip fractures. Another not listed are the drugs for gastroesophageal reflux.

[image]

What are the drugs that can be used to address bone health in Parkinson’s and what are the challenges in using them?

The swallowing challenges, along with slowed gut motility, and possible malabsorption should all be considered when choosing a drug to treat bone health in Parkinson’s disease.

There bone health drugs are called bisphosphonates and these can be taken each day in a pill or liquid formulation. These drugs include alendronate, ibandronate, and risedronate. Bisphosphonates stop the bone from being reabsorbed by the body. These drugs can prove challenging for people with Parkinson’s disease, as they must be taken early in the morning and only on an ‘empty stomach.’ Most prescribing healthcare practitioners recommend they not be taken with other medications, and this requirement can be challenging for those with Parkinson’s disease. Further, the requirement for a full glass of water and remaining upright and fasting for half an hour after each dose can be difficult if you have Parkinson’s disease.

One alternative approach to administering a bisphosphonate in Parkinson’s is by IV (intravenous). Zoledronic acid is administered once a year for three years. This approach has been associated with ~75% reduction in spine fractures and a 40% reduction in other fractures. Though data has been lacking specifically for Parkinson’s disease, there is a large ongoing multi-center trial on this drug.

An alternative medication approach has been using the drug Denosumab. This drug works on the immune system, and is called a monoclonal antibody. This drug is administered under the skin every six months, and should be avoided if you have kidney disease. One worrisome side effect may emerge when the drug is stopped, and it may lead to an unexpected rebound worsening in fractures.

[image]Here is a list of some of the medication treatments for osteoporosis.

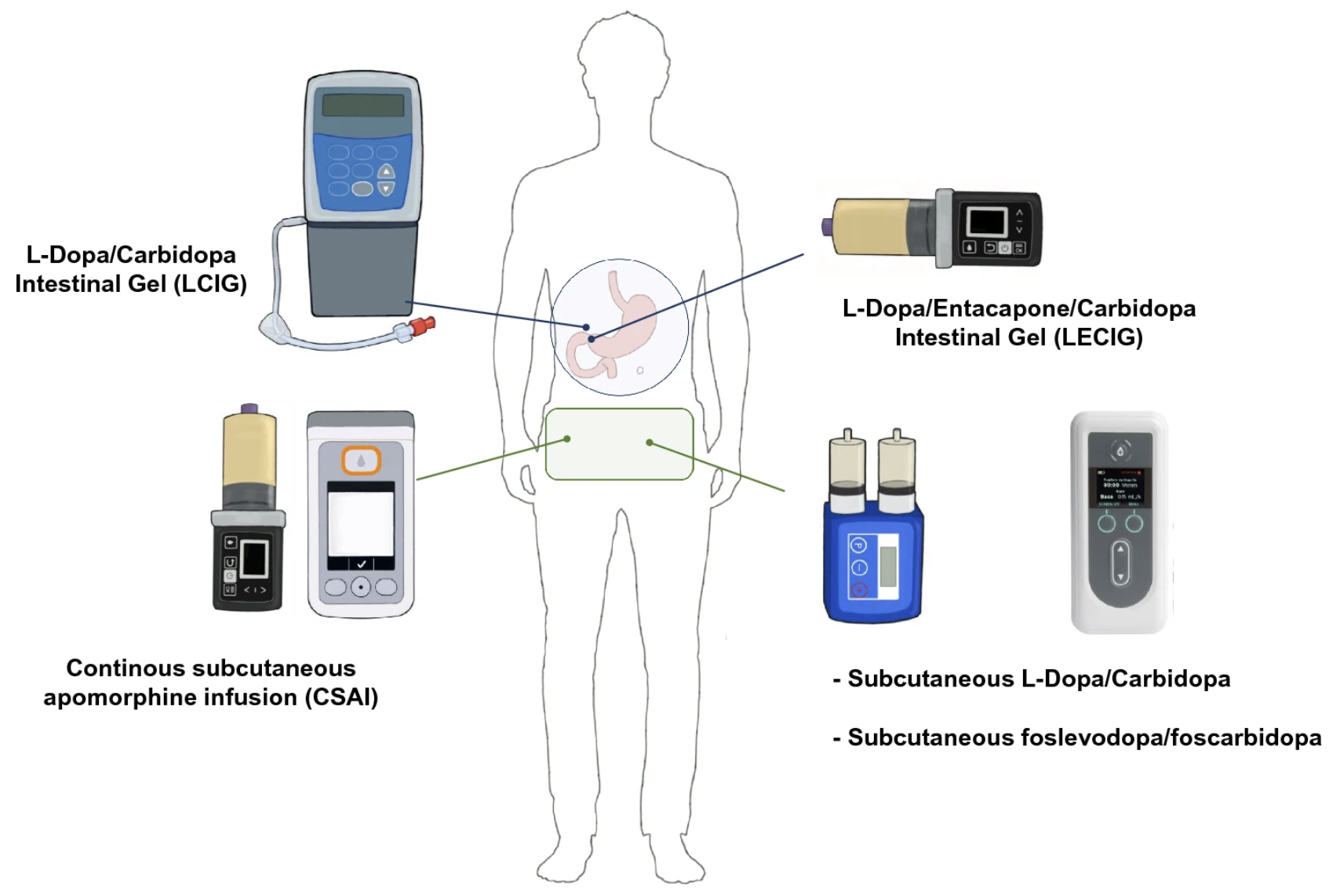

This is a picture by Antonini and colleagues that appeared in an excellent recent review article in the Journal of Neural Transmission about the emerging options when considering continuous dopamine delivery by pump.